|

Salmonid Information

Visit our Salmon Life Cycle Page for more information and photos

Salmon Identification

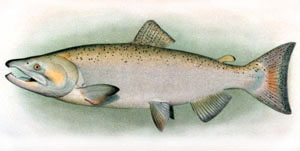

Chinook Salmon, Oncorhynchus tshawytscha Chinook Salmon, Oncorhynchus tshawytscha

Other names: king, tyee, blackmouth (immature)

Average size: 10-15 lbs, up to 135 lbs

Fall spawner; fall, spring, and summer runs

Chinook salmon are the largest of the Pacific salmon, with some individuals

growing to more than 100 pounds. These huge fish are rare, as most mature

chinook are under 50 pounds.

Spawning - Most chinook spawn in large rivers such as the Columbia and Snake,

although they will also use smaller streams with sufficient water flow. They

tend to spawn in the mainstem of streams, where the water flow is high. Because

of their size they are able to spawn in larger gravel than most other salmon.

Chinook spawn on both sides of the Cascade Range, and some fish travel hundreds

of miles upstream before they reach their spawning grounds. Because of the

distance, these fish enter streams early and comprise the spring and summer

runs. Fall runs spawn closer to the ocean and more often use small coastal

streams. All chinook reach their spawning grounds by fall, in time to spawn.

Rearing - Chinook fry rear in freshwater from three months to a year, depending

on the race of chinook and the location. Spring chinook tend to stay in streams

for a year; fish in northern areas, where the streams are less productive

and growth is slower, also tend to stay longer. Rearing chinook fry use mainstems

and their tributaries.

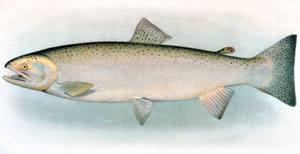

Coho Salmon, Oncorhynchus kisutch Coho Salmon, Oncorhynchus kisutch

Other names: silver

Average size: 6-12 lbs, up to 31 lbs

Fall spawner

Coho are a very popular sport fish. This species uses coastal

streams and tributaries, and is often present in small neighborhood streams.

Coho can even be found in urban settings if their needs of cold, clean, year-round

water are met.

Spawning - Coho spawn in small coastal streams and the tributaries of larger

rivers. They prefer areas of mid-velocity water with small to medium sized

gravels. Because they use small streams with limited space, they must use

many such streams to successfully reproduce, which is why coho can be found

in virtually every small coastal stream with a year-round flow.

Returning coho often gather at the mouths of streams and wait for the water

flow to rise, such as after a rain storm, before heading upstream. The higher

flows and deeper water enable the fish to pass obstacles, such as logs across

the stream or beaver dams, that would otherwise be impassable.

Rearing - Coho have a very regular life history. They are deposited in the

gravel as eggs in the fall, emerge from the gravel the next spring, and in

their second spring go to sea, about 18 months after being deposited. Coho

fry are usually found in the pools of small coastal streams and the tributaries

of larger rivers.

Cutthroat Trout, Oncorhynchus clarki Cutthroat Trout, Oncorhynchus clarki

Other names: sea-run cutthroat, harvest trout

Average size: 1-4 lbs, up to 6 lbs

Spring Spawner: upriver migration in late summer and fall

Of the 13 subspecies of cutthroat trout indigenous to North America, only

the coastal cutthroat is anadromous. But coastal cutthroat have complex life

histories, and not all fish are anadromous. In any given body of water, some

may migrate to sea, while others become resident fish. In fact, the offspring

of resident fish may migrate, while the offspring of anadromous fish may "residualize."

Spawning - Sea-run cutthroat spawn over a long period, from winter through

May. They seek smaller streams where the flow is minimal and the substrate

is small, almost sand. They prefer the upper-most portions of these streams,

areas that are too shallow for other salmonids.

Rearing - Most cutthroat rear in-stream for two to three years before first

venturing into salt water. Emerging fry are less than an inch long, and are

poorly able to compete with larger coho and steelhead fry for resources. To

compensate, cutthroat fry use headwaters and low-flow areas that coho and

steelhead avoid.

Unlike other anadromous salmonids that spend multiple years feeding far out

to sea, cutthroat prefer to remain within a few miles of their natal stream.

They do not generally cross large open-water areas. Some will overwinter in

freshwater and only feed at sea during the warmer months. In rivers with extensive

estuary systems, cutthroat may move around in the inter-tidal environment

feeding, plus run up-river or out to sea on feeding migrations, wherever their

nose tells them the food is. Protected estuaries and bays are

excellent cutthroat habitat.

Steelhead Oncorhynchus mykiss Steelhead Oncorhynchus mykiss

Other names: steelhead trout, sea-run rainbow trout

Average size: 8-11 lbs, up to 40 lbs

Spring Spawner: summer and winter runs

Steelhead and rainbow trout are the same species, but rainbow are freshwater

only, and steelhead are anadromous, or go to sea. Unlike most salmon, steelhead

can survive spawning, and can spawn in multiple years.

Spawning -Steelhead spawn in the spring. They generally prefer fast water

in small-to-large mainstem rivers, and medium-to-large tributaries. In streams

with steep gradient and large substrate, they spawn between these steep areas,

where the water is flatter and the substrate is small enough to dig into.

The steeper areas then make excellent rearing habitat for the juveniles.

Like chinook, steelhead have two runs, a summer run and a winter run. Most

summer runs are east of the Cascades, and enter streams in summer to reach

the spawning grounds by the following spring. A few western rivers

also have established runs of summer steelhead. Winter runs spawn closer to

the ocean, and require less travel time.

Rearing - Steelhead fry emerge from the gravel in summer and generally rear

for two or three years in freshwater, occasionally one or four years, depending

on the productivity of the stream. Streams high in the mountains and those

in northern climes are generally less productive. Due to their faster growth,

hatchery steelhead smolt at one year of age.

Fry use areas of fast water and large substrate for rearing. They wait in

the eddies behind large rocks, allowing the river to bring them food in the

form of insects, salmon eggs, and smaller fish.

Salmon Facts

- Coho and sockeye are found in freshwater year-round; coho

in small coastal streams and sockeye in lakes. These fish are very susceptible

to poor water quality, such as high temperatures and pollution

- Salmon species have adapted to use virtually every part of every stream

in the northwest.-Big rivers are used by pink salmon in the lower reaches,

chinook in the mainstem and larger tributaries, coho in small tributaries, and steelhead

in the uppermost tributaries.

- Small streams are used by chum in the lower reaches, coho next, and cutthroat

in the headwaters.- A moving fry is much easier to see than a motionless one.

This is why salmon tend to spawn in parts of the stream that their offspring

use for rearing; the emerging fry do not have to travel far to find rearing

areas.

- The size of a salmon is usually related to its age. Pink salmon are the

smallest fall-spawning salmon and are also the youngest, at two years. Chinook

can live up to nine years, the longest, which is why some chinook can grow

to over 100 pounds. Cutthroat, which live longer than pinks, are smaller because

they live in less productive areas of the watershed.

- There is a sixth fall-spawning salmon, the masu, or cherry salmon, which

is found only in Asia. This fish occupies the same niche that the sea-run

cutthroat trout occupies in North America

- Steelhead and rainbow trout are the same species of fish; rainbow are the

freshwater form, and steelhead the anadromous form.

- Steelhead and cutthroat trout were recently added to the salmon genus,

Oncorhynchus, from the trout genus, Salmo. Also, the scientific name of steelhead

changed from Salmo gairdneri to Oncorhynchus mykiss.

Salmon Terms to Know

- Alevin - The lifestage of a salmonid between egg and fry. An

alevin looks like a fish with a huge pot belly, which is the remaining egg

sac. Alevin remain protected in the gravel riverbed, obtaining nutrition from

the egg sac until they are large enough to fend for themselves in the stream.

- Anadromous - Fish that live part or the majority of their lives in saltwater,

but return to freshwater to spawn.

- Emergence - The act of salmon fry leaving the gravel nest.

- Fry - A juvenile salmonid that has absorbed its egg sac and is rearing in

the stream; the stage of development between an alevin and a parr.

- Kype - The hooked jaw many male salmon develop during spawning.

- Parr - Also known as fingerling. A large juvenile salmonid, one between a

fry and a smolt.

- Smolt - A juvenile salmonid which has reared in-stream and is preparing to

enter the ocean. Smolts exchange the spotted camouflage of the stream for

the chrome of the ocean.

- Substrate - The material which comprises a stream bottom.

Pacific Salmon

Protecting and preserving wild salmon has become a popular

topic within the last several years, both in the media and in natural resource

agencies. Although the numbers of wild salmon have been declining for more

than a century, the debate over how to address the problem has been infused

with a new sense of urgency. A landmark study in 1992 titled "Pacific

Salmon at the Crossroads: Stocks at Risk from CA, OR, ID and WA," identified

214 wild spawning salmon stocks that were at risk of extinction or of special

concern, including 17 stocks that were already extinct. Protecting and preserving wild salmon has become a popular

topic within the last several years, both in the media and in natural resource

agencies. Although the numbers of wild salmon have been declining for more

than a century, the debate over how to address the problem has been infused

with a new sense of urgency. A landmark study in 1992 titled "Pacific

Salmon at the Crossroads: Stocks at Risk from CA, OR, ID and WA," identified

214 wild spawning salmon stocks that were at risk of extinction or of special

concern, including 17 stocks that were already extinct.

When we talk about the survival of wild salmon, we are also talking about

the survival of the natural heritage of the Pacific Northwest. When thousands

of mature salmon spawn and die, they do far more than produce another generation.

This source of nutrition, arriving in the fall, allows many animals to survive

the harshness of winter. Where salmon runs have become extinct, the local

ecosystem suffers. Species such as bear, eagle, mink and river otter suffer

large population losses. Other species show less dramatic, but significant

declines. The result is a permanently altered ecosystem. Wild salmon are quite

literally the energy that fuels our natural environment.

Each individual stock of salmon is important. A chinook salmon from one river

may be quite different genetically from a chinook of another river. This vast

genetic diversity has allowed salmon to survive for two million years by helping

them adapt to a specific local watershed or adjust to a changing one. They

have endured floods and droughts, disease, volcanic eruptions, and even ice

ages. Every stock lost to extinction is a loss of important genetic information,

leaving the remaining fish less able to survive.

We are fortunate to have Pacific salmon in California, and often in our backyards.

These fish are naturally found only in the northern Pacific Ocean, from California

to Alaska, and from Siberia to Japan. Wild salmon are a natural treasure,

and those of us who choose to live in the Pacific Northwest have an obligation

to ensure their continued survival.

Salmon Information Links

Information courtesy of the Washington Department of Fish & Wildlife, visit their website for even more salmon information and images

Images this page courtesy of:

Please contact us for more info.

|